The action-horror film Battle Royale was a huge box-office hit in Japan in December 2000, grossing 212 million yen during its first weekend, and gaining theatrical release in twenty-two countries worldwide, though it was banned in several. Kinji Fukasaki’s film, based on the novel by Koushun Takami, tells the story of a class of high-school students in a dystopian futuristic Japan, who are kidnapped by the army, taken to a small island and forced to fight each other to the death until only one survivor remains. This is a state-decreed blood-game, instituted after the mutiny and walk-out of 800,000 students across Japan.

This plot was appropriated by the American author Suzanne Collins in a series of novels for young adults, starting with The Hunger Games in 2008. While Collins laid herself open to accusations of plagiarism in lifting the basic plot from her model, setting and tone from her model, she should be given credit for her brilliant development of the dystopian setting to show a neo-feudal society stratified into a psychopathic ruling class, a narcissistic metropolitan elite, and a starving peasantry forced to pay tribute to the state by sacrificing their children in its hi-tech annual blood games. We follow the fortunes of Katniss Everdeen, chosen as one of twenty-four annual ‘tributes’ as they fight each other to the death in a high-tech landscaped arena of several kilometres in dimension. In a sickening twist on the vogue for ‘Reality TV’ — and there’s a rudimentary precursor of this idea in the original as well — in Collins’ version the ‘Hunger Games’ are broadcast live across the country in the premier media event of the year, and the winners turned into pampered celebrities.

This archaeo-futuristic setting, combined with accessible characterisation and suspenseful plotting, contributed to the novel’s huge and immediate success. In March 2009 the production company Color Force acquired the film rights to The Hunger Games and immediately entered into a distribution agreement with Lions Gate Entertainment. Collins collaborated in the adaptation of her novel for the screen, and went on to produce two sequels, Catching Fire and Mockingjay, also made into successful movies.

The changes made by Collins should not be accounted plagiarism but a creative reimagining of the Battle Royale plot, which mitigates some of the crude horror of the original by infusing it with archetypal personal dramas and memorable screen-images, while bringing the same theme of state-sanctioned child-sacrifice to a global audience.

There is an intriguing discussion of the sociological function of blood games in the document known as The Report From Iron Mountain (1967), which is either a leaked government think-tank report, or a satire written by the publisher Leonard C Lewin in the form of such a report. The document, whatever its provenance – and there doesn’t seem to me to be anything very satirical about it – discusses possible surrogates for the non-military functions of war in human culture as it explores questions implied in its title, On the Possibility and Desirability of Peace.

In a discussion of the motivational function of war as a model for collective sacrifice, the authors take us on an excursion to Meso-America:

A brief look at some defunct premodern societies is instructive. One of the most noteworthy features common to the larger, more complex, and more successful of ancient civilizations was their widespread use of the blood sacrifice. If one were to limit consideration to those cultures whose regional hegemony was so complete that the prospect of ‘war’ had become virtually inconceivable – as was the case with several of the great pre-Columbian societies of the Western Hemisphere – it would be found that some form of ritual killing occupied a position of paramount social importance in each. Invariably, the ritual was invested with mythic or religious significance; as with all religious and totemic practice, however, the ritual masked a broader and more important social function. (p40)

While the purpose of the Report is to explore the implications of a successful transition to an oligarchical collectivist World Government under a global Pax Americana, I would suggest that in the era of nuclear weapons these conditions already apply in the technologically advanced countries, where the population can no longer conceive of war on their own soil against genuinely threatening enemies. While Western society functions against a backdrop of permanent ‘war’ in far-off places, these are in truth, to paraphrase Jean Baudrillard, merely atrocities masquerading as wars. Without military conscription, and with most of the killing done from the air, often using pilotless drone aircraft, these ‘wars’ can no longer fulfil the life-and-death sociological function of conflict in the past, and so the need for a “credible substitute [...] capable of directing human behaviour patterns” remains. Alternative models must be found, whether real or fictive, capable of motivating basic allegiance through an “immediate, tangible and directly felt threat of destruction, [justifying] the need for taking and paying a ‘blood-price’ in wider areas of human concern”.

The Report goes on to lament the poverty of futurological thinking within government as it notes with interest the rise of such models in futuristic fiction.

Games theorists have suggested, in other contexts, the development of ‘blood games’ for the effective control of individual aggressive impulses. It is an ironic commentary on the current state of war and peace studies that it was left not to scientists but to the makers of a commercial film to develop a model for this notion, on the implausible level of popular melodrama, as a ritualized manhunt. (p54)

This would appear to be an allusion to Elio Petri’s La Decima Vittima, or The 10th Victim (1965), in which a blood-game called ‘The Big Hunt’ has been instituted as a surrogate for large-scale conflict. The plot, in common with Battle Royale and Hunger Games, seeks to create effect by inverting traditional roles, as the beautiful Caroline Meredith (Ursula Andress) homes in on her tenth victim, Marcello Poletti (Marcello Mastroianni); in later iterations of the theme, the sense of a perversion of the natural order is taken to the next level by casting children as cold-blooded killers as well as victims.

Principal photography on The Hunger Games began in May 2011 in North Carolina, and continued to September.

On 22nd July 2011, on the tiny, picturesque island of Utøya on Tyrifjorden lake about an hour’s drive from Oslo, Norway, some five hundred and fifty teenagers between the ages of fourteen and seventeen were taking part in a summer camp under the auspices of the AUF, the Workers Youth League affiliated to the Norwegian Labour Party. News had just reached the camp of the bombing of government buildings in Oslo. Eight people were reported to have died and many more to be badly injured. Since many of the teenagers’ parents worked for the government, a number of them requested to return home, but they were denied permission on the grounds that they would be safer on the island.

The prominent politician Gro Harlem Brundtland, known as the ‘Mother of the Nation’ was visiting the camp to meet the young people, and left for the mainland at around four in the afternoon. A little after five, Anders Behring Breivik, dressed as a police commando and carrying a heavy case of weapons and ammunition, crossed by ferry to the island of Utøya. Once on the island, Breivik immediately set about gunning down the teenagers and hunting them all over the island. Some of the terrified students threw themselves into the icy water to try to swim the six hundred meters to the mainland. Others found a rowing boat and tried to escape. The gunman — or men, since some survivors reported having seen at least two and as many as five, dressed like Breivik in wetsuits and police combat gear — slaughtered them in huddles on the coast, and picked them off in the water.

The youth-camp leader, together with seven or eight other adults, abandoned the students to their fate, commandeering the ferry and fleeing without making any attempt to save anyone. Desperate calls from mobile phones to police and parents brought no help. The slaughter continued for over an hour. Press helicopters were hovering over the island, filming the action, long before any help arrived – security forces landing on the island only after Breivik had communicated his readiness to surrender.

It is hard to imagine a greater sense of abandonment. As one character in Battle Royale says, “Someone will come, because of the gunshots.” Her friend answers, “No one is going to save you. That’s just life.”

By the time security forces got to the island, scores of young people lay dead or dying. As reported by independent journalist Ole Dammegård, gunshots continued to be heard by witnesses on the mainland for at least five minutes after Breivik’s surrender. After the executioner was in custody, and while victims were bleeding to death on the island, ambulances were prevented by officials from crossing to the island for ‘security reasons’.

The final death count was sixty-nine, with more than a hundred injured and maimed.

The abysmal failure of the security services to bring any aid to the teenagers is made even harder to understand by the fact that Delta force units had conducted a drill of a mass-shooting on one of the many islands on Tyrifjorden lake only hours beforehand.

By the same amazing coincidence that so often echoes around the cities of Europe and America, the bombing in Oslo also occurred shortly after the conclusion of a drill foreshadowing the same event.

The Hunger Games opened in cinemas on 21st March 2012, setting box-office records for both opening day and opening weekend gross for a non-sequel. It grossed $695.2 million, making it the ninth-highest-grossing film of 2012.

Three weeks later, the trial of Anders Behring Breivik began, continuing until 22nd June. Breivik refused to recognise the authority of the court or to show any remorse for his actions, which he justified as politically necessary to oppose the planned deconstruction of Norwegian society through mass immigration: that’s why he targeted of the youth wing of the leftist Norwegian Labour Party. In an inversion of the usual pattern, the prosecution pushed for a verdict of insanity, while Breivik and his defence team opposed it, demanding the court recognise the distinction between ‘clinical insanity’ and ‘political extremism’. Breivik himself expressed contempt for any legal process that did not result either in death or acquittal. He admitted all offences, and proudly confessed that he had intended to kill everyone on the island – but pleaded not guilty on the grounds of political ‘necessity’.

Breivik’s political speeches and callous comportment during the trial and the police reconstruction of his murders on the island did much to discredit and paralyse nationalist concerns about multiculturalism and mass immigration. Breivik published a ‘manifesto’ on Facebook, full of anti-Moslem rants and plagiarised passages from the Unabomber’s manifesto published in the The Washington Post in 1995. Curiously, this was only uploaded, according to Dammegård, after Breivik’s arrest.

Sentence was passed on 24th August 2012. Breivik was adjudged sane and sentenced to indefinite detention.

There were significant policy changes in the aftermath of the massacre. Norway had recently announced its withdrawal from ‘War on Terror’ bombing raids on Libyan and Afghani targets. Not long afterwards, in a complete policy reversal, Norway became an honorary member of NATO. Jens Stoltenberg, the prime minister whose task it was to play the hero and unify the country around this tragedy, was ultimately rewarded by his appointment as NATO’s Secretary General.

The Dark Knight Rises, the final film in Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy, premiered in New York on 16th July 2012 and was released in the US and UK on 20th July. Viral publicity campaigns, added to the huge impact made four years earlier by the second film in the trilogy, The Dark Knight, ensured that great excitement and anticipation surrounded the release. Across America, screenings were scheduled to begin at the earliest possible moment, on the stroke of midnight.

Half an hour into the movie, at a multiplex cinema in Aurora, Colorado, a young man named James Holmes entered Theatre 9 clad in body armour and a gas mask, where he set off tear gas grenades and opened fire on the audience with a tactical shotgun and a semi-automatic rifle. Twelve people were killed and a further seventy injured.

The carnage inside the cinema was terrible, and the chaos intensified as police burst in, not knowing that the shooter had already surrendered outside the cinema. The movie kept playing, the deafening soundtrack making communication impossible and all but drowning out the screams of the victims. Outside, the killer removed his helmet to reveal a mop of dyed-red hair — a tribute, allegedly, to Batman’s psychopathic antagonist, The Joker, a character brought unforgettably to life by the actor Heath Ledger in The Dark Knight. Ledger had died from a compounded drug interaction soon after the completion of filming, and so the Joker character was written out of the sequel in deference to his performance. Ledger didn’t live to see the final edit of The Dark Knight, but four years later the psychological impact of his interpretation was still making ripples.

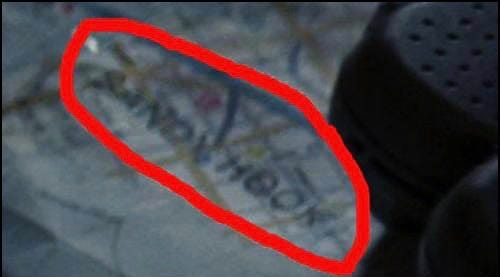

The attack began about thirty minutes into the screening. About an hour further into the film, something very strange happens — though nobody would notice it until much later: the name

is flashed up on the screen.

It appears onscreen for about a second and a half on a map of Gotham City, close to the point marked ‘Strike Zone 1’, where the police expect the next of the terrorist Bane’s attacks to take place.

In the original comics and novels, and in Nolan’s Batman Begins, the Southern tip of Gotham City is called ‘South Hinkley’. The name ‘Sandy Hook’ appears nowhere in the entire Batman franchise.

The name-change didn’t mean anything to anyone at the time, and attention was only drawn to it six months later, after a disturbed teenager shot and killed twenty young children and six adults at an elementary school in Newtown, Connecticut, on the morning of 14th December 2012.

No reason has been ascertained for the name change on the map. But, to anyone but the most unthinking coincidence-theorist, the location of a future mass shooting appearing on a cinema screen during another mass shooting has to make you wonder about the provenance of such events. You sense, for a moment, the presence of demonic trickster spirit lurking deeper than an actor’s psychotic performance or the induced psychosis of a brilliant but distressed student.

But then you dismiss it because it doesn’t make sense.

How could someone involved in the production of Nolan’s film know in advance about the tragedy at Sandy Hook?

And about the Aurora massacre too, without which the irony would be lost?

But it is a measure of the strange and paranoid times we live that three weeks’ after the Newtown horror, schools in the town of Narrows, Virginia, closed for a day to review security protocols, after an online article pointed out that the name ‘The Narrows’ features on the Gotham City map in the film, close to the ‘Strike Zone 2’ marker.

The Sheriff of Giles County told the press that the information had to be taken seriously.

Bizarre coincidences, after all, have proved lethal in the past.

2012 was the year the world didn’t end. Much had been made of a much hyped prophecy that it would, said to be implied by the terminal date of the Mayan Long Count, falling on December 21st 2012.

As the year drew to its close but the world didn’t, it seemed that pre-Colombian prophecies would prove less relevant to our own times than reminders of the archaic practice of child-sacrifice.

https://thelethaltext.me

I've been discussing how to avoid a human "mouse utopia" with friends https://search.brave.com/search?q=%22mouse+utopia%22 (although the experimenters didn't try varying the environment enough IMO, say by opening up new areas and closing other off, also by varying the food supply, both are things found in our modern environment).

Evidently our current elites also suffer from a tremendous lack of imagination as well as empathy.