EINSTEIN AND EMPTINESS

"No one quite knows why..."

“It seems to me that the arguments which have led up to the theory (Relativity), and the whole state of mind of most physicists with regard to it, may some day become one of the puzzles of history.” Professor P W Bridgeman (1936)

Tesla was effectively sidelined by 1905, and at that moment a new scientific celebrity appeared. While Tesla was running into a financial brick wall and being robbed of his radio patents, a young man named Albert Einstein had been settling into a job as assistant patents inspector in Zurich, Switzerland. His new job gave him the time and resources to study and write, and in 1905 he submitted five papers to peer-reviewed academic journals. All five were accepted for publication.

1905 is always described as Einstein’s annus mirabilis, and indeed there is something miraculous about his instant success. H C Dudley, in his 1976 essay ‘The Personal Tragedy of Albert Einstein’, argues that academia’s enthusiastic embrace of Einstein “contrasts the treatment accorded the young unknowns of today who take unorthodox approaches to science. The present peer review systems are so stifling that any manuscript so iconoclastic as Einstein’s initial papers would now have little chance of appearing in any ranking journal. This is particularly true in physics, and especially so in the United States. […] Of the five papers published by young Einstein in 1905, three were destined to bring him fame. These three papers would by 1940 be recognized as basic to the physical sciences.”

As well as the five published papers, the year was crowned with the award of his doctorate by Zurich University. In 1908 he was given a lectureship at Bern, in 1911 a professorship at Berlin, and in 1912 he was made Professor of Theoretical Physics at Zurich. In 1913 he was elected a member of the Prussian Academy, and appointed as Director of the new Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics (taking up the post in 1917). In 1920 he was elected to the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, and so it goes on, Einstein’s cushioned academic path granting him the status, comfort and freedom to pursue his thought experiments and calculations, in stark contrast to the rocky road Tesla was condemned to walk. Just as the finance had swerved to Marconi, the academy now swerved to Einstein.

In 1916 Einstein produced his Theory of General Relativity, a metaphysical cosmology which excluded the essential discoveries of the electrical movement and enthroned gravity as the sole architect of the universe. The theory failed to define mass, energy or gravity. No experiments to test it were conducted until a series of solar eclipses created opportunities to confirm his predictions about observed star positions based on the gravitational curvature of space. Einstein was promoted by the British establishment in the person of Sir Arthur Eddington, whose 1919 eclipse observations were massively hyped in both the London and New York Times as proving the theory of Relativity, despite other explanations of the phenomenon being available. Einstein was hailed as the new Copernicus, Galileo and Newton rolled into one, and awarded a Nobel Prize in 1921. A commemorative edition of the journal Nature was published in his honour, and he embarked on a world tour. In America he was given a triumphal ticker-tape reception on Wall Street, visited the White House, and lectured at Columbia and Princeton.

In London he was feted by the aristocracy, presented to prominent figures across the intellectual establishment, and given the podium at King’s College. After visiting Palestine, Ceylon, and Singapore, he was honoured to be received by the Emperor and Empress of Japan at the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, in front of a crowd of thousands of onlookers.

“No one knows quite why,” wrote the British novelist C P Snow in his 1967 retrospective in Commentary Magazine, “but he sprang into the public consciousness, all over the world, as the symbol of science, the master of the 20th-century intellect, to a large extent the spokesman for human hope. It seemed that, perhaps as a release from the war, people wanted a human being to revere. It is true that they did not understand what they were revering. Never mind, they believed that here was someone of supreme, if mysterious, excellence.”

It is left to Dudley to ask “an obvious question: Why should a rather obscure mathematical theorist’s prediction of an obscure astronomic event generate such world-wide interest, producing a ticker-tape parade down New York’s Wall Street in 1921?”

Well, no one quite knows why — though the location of the parade might just be a clue. In fact it’s obvious that Einstein, regardless of the legitimacy or otherwise of his methods, did not ‘spring’ anywhere but was picked up and decisively inserted into public consciousness by a huge public relations campaign. The new advertising gurus such as Edward Bernays and Ivy Lee had already shown that they could sell the public anything from cigarettes to world war. Now they would sell them a new, mystical version of science which they could neither hope to understand nor benefit from in any way.

Was Einstein promoted as a surrogate for the figure of charismatic scientific genius embodied by Nikola Tesla? It is tempting to see his meteoric rise as a continuation of the systemic spasm that erased Tesla’s influence. With Tesla taken down, his position in the culture needed to be filled. The system needed not just to suppress his work but to provide a substitute to soak up the adulation that had surrounded him. It needed to ground that current.

There was widespread scientific objection to the installation of Einstein’s theories as the new orthodoxy, and not, as the public has been taught to think, only from ‘Nazi’ scientists. Opposition to Einstein was sharpened by the media circus surrounding the eclipse experiment and the Nobel Prize, the sense of a short-circuited scientific process and a forced consensus around Relativity. Anyone drawing attention to Einstein’s alleged academic dishonesty or criticizing his theories ran the risk of being labelled an antisemite. The meeting of scientists at the Berlin Philharmonic in August 1920 and the debate at the Society of German Scientists and Physicians in Bad Nauheim bred such acrimony that the scientific issues were buried under racial and political controversy. One scientist had his life threatened; another was prevented from traveling to Berlin by the Czech government. Philipp Lenard, Johannes Stark and other experimentalists committed to a ‘Deutsche Physik’ were lambasted in the international press (continuing to the present day, as in this long and unrelenting hit piece in the Scientific American). Einstein benefitted immensely from the heavily publicized and propagandized opposition of so-called ‘Nazi’ scientists.

Academics across Europe and America found that it was a very bad career move to argue against Relativity. “Relativity is now accepted as a faith,” wrote R A Houstoun in his ‘Treatise on Light’ (1938). “It is inadvisable to devote attention to its paradoxical aspects.” Some even called it the ‘Einstein Terror.’ The phenomenon was at its most extreme in the Soviet Union, where critics of Einstein such as Yuri Brovko were subjected to psychiatric coercion, thrown into locked wards and pumped full of mind-destroying drugs. To advance any alternative theory was condemned as both antisemitic and anti-Marxist.

The consistent suppression of oppositional voices makes this a difficult terrain for any academic historian. “If one wishes to study the thinking of those who early opposed the relativistic theories (and there were many!) it becomes a major research project even to learn of the authors of such heresy. The usual abstracting services are strangely silent,” comments Dudley, who goes on to list some of the most significant books published in opposition to the new science, directing us towards authors such as Charles L. Poor, Gravity Versus Relativity (1922); Arthur Lynch, Science: Leading and Misleading (1927) and The Case Against Einstein (1932); and J.J. Callahan, Euclid or Einstein? (1931). In 1931 a hundred scientists and philosophers contributed to a volume denouncing Einstein and his theories.

The outrage centered on Einstein’s casual excision of the aether and Faraday’s lines of force from the field of physics — effectively denying the basic premises of the science of electromagnetism. The concept of an all-pervasive medium enabling the propagation of light through the universe had been continuously present throughout human history. From the akasha of Vedic philosophers to the aether of the pre-Socratic Greeks and the quintessence of the alchemists, humanity had intuited the reality of an invisible, all-pervasive substrate of matter. In the scientific age, from Descartes to Newton to Huygens to Maxwell, the necessary existence of a medium for the propagation of light — the luminiferous aether — was assumed. Indeed the existence of a ‘subtle medium’ had been demonstrated nearly three centuries earlier, in 1644, by the radiative transfer of heat through a Torricelli vacuum (Evangelista Torricelli, 1608-1647), proving the plenists right: even an air vacuum contains some kind of medium through which energy can travel.

Isaac Newton did not, contrary to stereotype, conceive of an empty, mechanical universe ruled by gravity. He described the effects of gravity only in mathematical terms, and understood that it was not at that stage possible to frame a hypothesis as to its underlying ‘cause’: but a cause it must have, which Newton ascribed to “a most subtle Spirit which pervades and lies hid in all gross bodies; by the force and action of which Spirit the particles of bodies mutually attract one another at near distances, and cohere, if contiguous; and electric bodies operate to greater distances, as well repelling as attracting the neighboring corpuscles; and light is emitted, reflected, refracted, inflected, and heats bodies; and all sensation is excited, and the members of animal bodies move at the command of the will, namely by the vibrations of this Spirit, mutually propagated along the solid filaments of the nerves, from the outward organs of sense to the brain, and from the brain to the muscles. But these are things that cannot be explained in a few words, nor are we furnished with that sufficiency of experiments which is required to an accurate determination and demonstration of the laws by which this electric and elastic Spirit operates.”

This, significantly, is no footnote or buried paragraph but the concluding passage of the Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687).

With the discoveries of Faraday and Crookes and the birth of the science of electromagnetism, it was now possible to answer Newton’s call and formulate exactly such a hypothesis. Conrad Razan, in his comprehensive History of the Aether Theory (2008), states unambiguously that with the Michelson-Morley experiment in 1887 the aether ceased to be a hypothesis and became a scientific reality. ‘Aether drift’ was indeed detected in the experiment of 1887, albeit at a lower value than predicted, a result which is dishonestly reported by orthodox sources as conclusively disproving the aether’s existence — as if a single experiment could do that in any case. Dayton Miller’s well-designed experiments in the twenties, and Roland de Witte’s in the nineties, confirmed over and again the existence of this pervasive subquantic medium without which the forces of gravity and electromagnetism (including light) could not be conveyed, and which puts ‘spooky action at a distance’ to rest. But Miller’s work came after the Einsteinian revolution and was ignored. De Witte was never allowed to publish his findings in a physics journal, and eventually succumbed to depression and died young.

Einstein’s dismissal of these criticisms as ‘superficial’ was a truly staggering choice of word. No wonder there was outrage, whether from German scientists or American, French or British. The Maxwell-Heaviside equations, the basis of the entirety of electro-magnetic science and technology, require the existence of an aether, as indeed does the common sense so derided by theoretical physicists: a wave, by definition, cannot propagate through nothing.

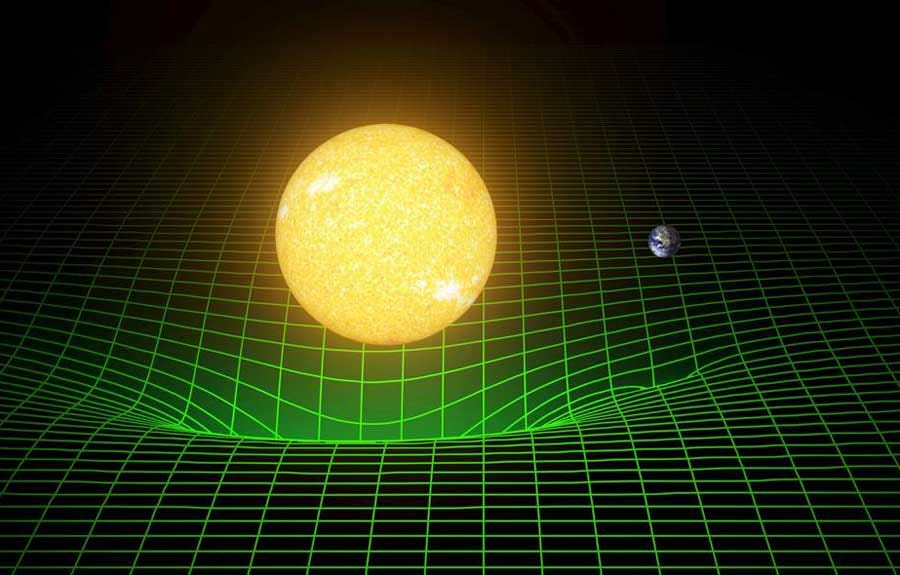

Einstein had compensated for the aether by inventing the surreal notion of ‘curved space’. This concept would appear, prima facie, absurd. I know – we’re supposed to say ‘counterintuitive’. Tesla, for one, wasn’t buying that cover for the new theory’s glaring flaws. He needed to call on none of his famous rhetoric and dismissed it in a single, plain sentence:

“I hold that space cannot be curved, for the simple reason that it has no properties.”

A priori: if space can be acted upon and distorted, then it is not space. Space is a metrical dimension, and does not have the attributes of matter. In order to be curved, space must be imagined as a substance, or ‘fabric’, rather than a dimension. To imagine Einstein’s concept we must change the meaning of the word; thus it is not space that curves, but language that is warped. Einstein offered no explanation as to how something could act upon nothing in this manner, or what might constitute his new meaning of the word ‘space’, or what word we should now use to denote the old meaning. He created his theory using a calculus developed by an obscure group of mathematicians in Germany in the mid-nineteenth century, which assumes that if parallel lines meet at infinity, a line projected in space must curve, and that a straight line is not, therefore, the shortest distance between two points. In General Relativity, the curvature is transferred to space itself, with gravity invoked as the cause.

These ‘metaphysical mathematicians’ also assumed the variability and reversibility of time, the interchangeability of mass and energy, and the non-existence of the aether — they assumed therefore the vacuous emptiness of cosmic space, a condition which had always been rejected by ‘plenist’ scientists and philosophers — Descartes, Newton, Huygens et al — as abhorrent to Nature. How the force of gravity — or light, or magnetism — could be propagated through such a vacuum is not dealt with in Einstein’s theory.

Dudley notes that while Einstein used legitimate observation-based methods in his papers on the photo-electric effect and Brownian movement, in developing Relativity he “allowed himself to become an integral part, in fact a leading disciple, of the ‘school’ which made use of metaphysical mathematics.”

Tesla was scathing. “Today’s scientists have substituted mathematics for experiments, and they wander off through equation after equation, and eventually build a structure which has no relation to reality.”

In interviews in the New York Sun and New York Times in 1935 Tesla called Relativity “a mass of error and deceptive ideas,” asserting that not a single one of its propositions had been proved. Relativity, he said, “wraps all these errors and fallacies and clothes them in magnificent mathematical garb which fascinates, dazzles and makes people blind to the underlying errors. The theory is like a beggar clothed in purple whom ignorant people take for a king. Its exponents are very brilliant men, but they are metaphysicists rather than scientists.”

“Einsteinian curved space and the rest of that stuff,” says the electrical engineer E P Dollard in his more down-to-earth manner, “is useless, it’s pure magic.”

By taking selectively from Newton and Maxwell and ignoring the work of Tesla and J J Thomson, Relativity becomes, in Dollard’s words, a ‘giant one-winged parrot’, a cuckoo-like parasite.

“Albert Einstein is in direct contradiction with the experimental researches of Nikola Tesla, and in complete ignorance of the experimental researches of J. J. Thompson. Einstein layed his egg in the nest of Faraday.” (The Theory of Anti-Relativity, E P Dollard)

‘Quantum mysticism’, Dollard calls it, its job — and Einstein’s role in particular — to make nonsense of the world and turn science into a Tower of Babel.

“…Through the lawyer-style skill of the Einsteinian physicists, all terms are erased that do not fit the chosen idea. It may be inferred that A. Einstein was not much of a mathematician, and by ignoring J. J. Thompson he was not much of a scientist. Not a mathematician, not a scientist, not an engineer, so just what was Albert Einstein anyway? He was a Mystic.

The mystical experience is the force which moves one to science. It is transitory. The mysticism dissolves into Science and then bears fruit as Engineering. Mysticism, as defined in my writing, is not transitory. It is continuous and thus hates Science. Without a mystery the mystic is no longer the priest. This is a Platonic epistemology. It is based upon faith, not upon reason. This is a necessity in Christianity, however in the majority of situations this faith is based upon nebulous reasoning. With lawyer-like skill its factors change meaning depending upon their position in space, time, or ‘attitude’. Platonic reasoning is ultimately totalitarian.” (Eric P Dollard, The Theory of Anti-Relativity)

And elsewhere: “Einstein was a media event. You might as well ask Santa Claus, or Bin Laden.”

Or William Shakespeare, for that matter, since the most famous paradox in the history of science appears to be a literary device — an oxymoron — as opposed to a scientific concept. ‘Curved space’ is a clever metaphor for the effects of gravity — a nice bit of poetry, that’s all.

The Theory of Relativity is not even strictly relativist: it fundamentally contradicts itself in its absolutist assumption of the velocity of light as a ‘speed limit’ on all forms of propagation. Tesla and Alexanderson had both worked with wave forms vastly exceeding luminal velocity, years before Einstein. In recent times, C.E.R.N. (Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire) has conducted superluminal particle experiments. But none of this can shake the priesthood, which blithely pretends not to notice.

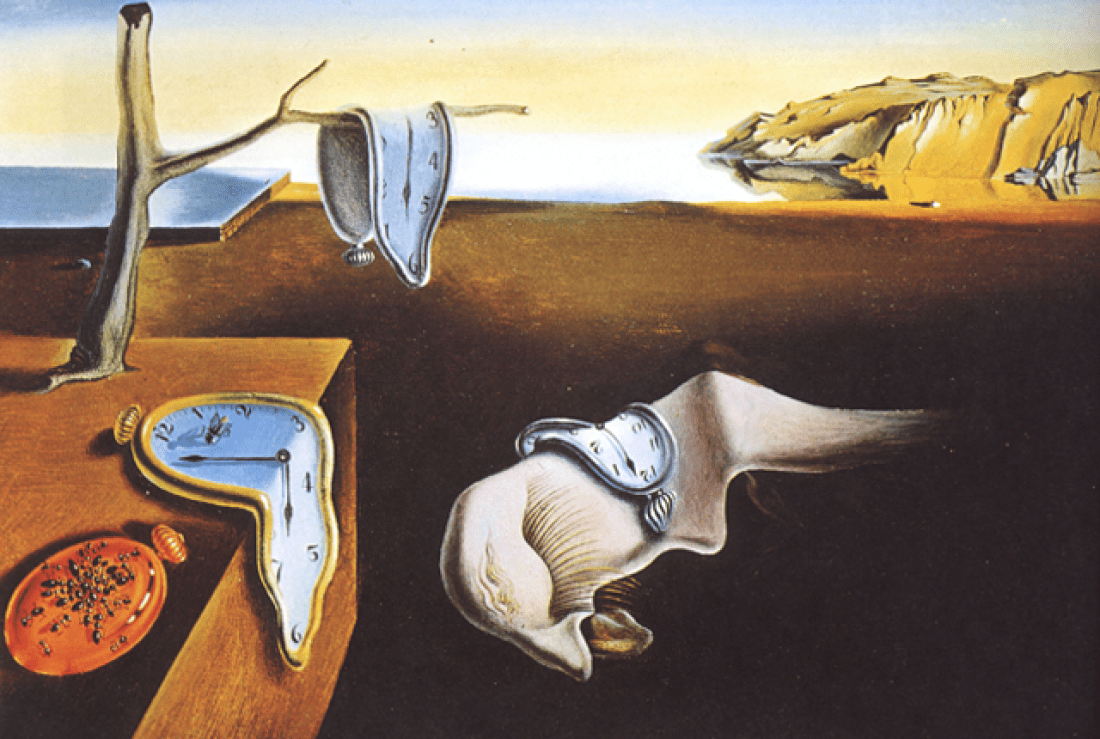

The imposition of the speed of light as a limit on all propagation stands out as an arbitrarily fixed element in what is supposed to be a formulation of universal flux. It had been disproved before it was even proposed. According to Dollard, the design of the Marconi transmitter at Bolinas 1912-17 itself refuted Einstein. The absolute limit on propagation leads, famously, to time dilation and time reversal, as other elements are forced to fall into place around this unyielding and artificial value. Time and space must both give way; even causation, the principle of all physics, must be sacrificed. Einstein himself tried to put the brakes on, but was bested in his debates with Neils Bohr and ultimately lost influence because he would not (to his credit) accept the idea of ‘acausality’ — which assumes that an event may arise spontaneously, requiring no initiating event — a doctrine which repudiates the foundations of science and takes theoretical physics into the realm, as Dollard says, of mysticism.

Einstein’s criticism of quantum mechanics conceded that it was an ‘effective’ theory; i.e., a theory that works well enough to predict effects, but fails in its explanatory effort. The fact that, with endless adjustments and ad hoc hypotheses, a formula can be made to ‘work’ does not prove that it is correct at the level of interpretation. To Einstein, quantum mechanics appeared incomplete, as if there was some underlying theory that was yet to be discovered.

The same can surely be said of Relativity, which reminds me in this respect of that ancient example of ‘effective’ theory which we find in Ptolemaic cosmology, which stood for a millennium and a half before being superseded by Copernicus, Galileo and Kepler. In Ptolemy we see again how the arbitrary adherence to one absolute element — here, the fixed earth — produces extraordinary theoretical convolutions, a whole celestial apparatus of equants, deferents and epicycles, geared and mounted on invisible crystal spheres, a vast astronomical machine constructed to explain planetary and sidereal motion. Ptolemaic cosmology was able make accurate enough predictions to enable navigation, but its invisible machinery was entirely imaginary. The modern equivalents of deferents and epicycles are the black holes, wormholes, gravitational waves and dark matter of theoretical physics.

In both Relativity and the Ptolemaic universe there is one element of the model that must be preserved at all costs. In the case of Ptolemy, the reasons for this attachment might seem obvious enough – religious and philosophical orthodoxy, sensory bias, the perspective of heavenly bodies moving around the earth. In the case of Einstein’s speed-of-light limit on all propagation in the universe, I suspect that it was adopted in order to exclude the superluminal forces known and used by Tesla, Steinmetz and Alexanderson. The speed of light, then, is the scalpel to excise electro-magnetism from modern cosmology.

Leaving – what?

A simulacrum.

With the metaphysical mathematicians, the territory no longer precedes the map. The century-long supremacy of Einsteinian physics is the clearest and perhaps the most important example it would be possible to find of the precession of simulacra, a leading edge of the twentieth century assault on the reality principle. It leads us nowhere but into Baudrillard’s desert of the real.

As a reversal of the scientific method, there has been nothing to prevent theoretical physics from giving birth to whole genealogies of mythological entities. At every turn, the necessity of ad hoc theorizing to maintain the central thesis gives rise to new particles and forces at will. These multiplying entities stand as evidence of the failure of the gravitational model, which singularly lacks the coherence and elegance of lasting science. While the theory gives no explanation of the nature or mechanics of the force of gravity, that doesn’t stop its practitioners from improvising endless cadenzas of gravity-inspired fictions: black holes and event horizons, dark matter, dark energy, singularities, string theory, WIMPS (weakly interacting massive particles), MACHOs (Massive Compact Halo Objects), neutron stars, gravitational collapse, gravitons, gravity waves, quantum gravity, gravitational lensing, gravitational radiation, the Schwarzschild Radius, anti-gravity, and quantum field theory, to name but a few. The never-ending chaos of the quantum model of reality grows less convincing with every patch and bypass. The latest vaunted ‘discovery’ of the Higgs-Boson particle via the collider at CERN, at a cost of more than 13 billion euros, is merely the latest such patch. CERN, whatever else it is, would appear to be a money sink, designed mainly to direct huge flows of money into the pockets of the technocrats and away from the knowledge-deprived masses. As for the oxymoronic ‘first image of a black hole’ in 2019, the contradiction implicit in that phrase tells you all you need to know about the wildly improvisational history of gravitational theory.

What will scientists in the future make of this surreal circus? Perhaps this will seem a darkly superstitious and benighted era, its cosmology chaotic, disconnected, and bleakly entropic. The universe exploded out of nothing, evolved precariously through accretion and collision, and will wind down again into deadness and darkness. Anything contradicting this etiolated vision of cosmic ennui is condemned as irrational sentimentality.

The suppression of aether physics has had dire consequences for 20th century science; the pound of flesh it cuts from electrical science is the heart itself. The work of aether and plasma theorists cannot be discussed in professional journals. Anything that refutes the mutually exclusive dogmas of Relativity or Quantum Mechanics will not be considered. Meanwhile Einstein continues to be promoted as the untouchable saint of the church of incomprehensible theories, designed to keep people in a primitive unscientific state.

In Baudrillardian terms, then, the Einsteinian universe would be a second order simulacrum, “of the order of malefice” — an image which “masks and denatures a profound reality”. In order to shake off its stagnation, science needs to rewind, ducking in under the compounding error and picking it up from 1919. In doing so it must throw off the idea of cosmic space as an empty, dead void, which in Dollard’s estimation is not just wrong — it’s a profane joke; a curse, even.

“The biggest keepers of Einstein and haters of Tesla are the astronomers. They’re married to the speed of light, it’s a religion, and space is empty and dead, it’s some kind of mathematical function, there’s nothing really there any more. Everything is reduced to some kind of base physical process. When a society’s understanding of nature and reality is reduced to the processes of physics, then it’s a Satanic society.”

"...a wave, by definition, cannot propagate through nothing."

When we raised the question of "the aether" as young students of physics, they patted us on the head and told us "that's the domain of philosophers, not scientists." Two electrical engineering degrees later, I still get the hairy eyeball when I question Einstein's "curved space." I never got the concept that "Gravity curves space, which causes gravity." The bowling ball on the spandex sheet demonstration is cute, but distracts from the obvious circular logic. Perhaps that's why they call it "curved" space.

You've done an excellent job telling the truth about a difficult subject with good prose. The propaganda is indeed strong and has had a century to cement itself in place.