DOUBLE-HEADED SNAKE

A hundred years it took, maybe two, but when it struck it was fast, closing like a sprung trap.

Ut crashed out in the middle of the day in the little hut he’d built at the edge of his field. Hung over on Lao Khao, the cheap, dirty rice spirit that is everywhere in these parts, he’d grown dizzy working in the sun.

He felt so sick he didn’t even lean his blade against the wall next to the door as he usually did, just threw himself down on the mat with one arm cushioning his face, his fingers loose around the wood of the handle. Then he’d rolled over onto his back, and let go of it.

The snake was already in there, he just didn’t see it.

It was sugar time, when the farmers harvest their crops with big machines that drum and howl deep into the night, their lights creating pools of strange, shifting shadows. Others set fire to their fields instead, to burn off the dense, dry foliage, leaving the clumps of canes standing free, before bringing in a ragtag team of workers, cheaper than the machine. The practice is technically illegal, so they sometimes do the burn-off at night; an eerie sight in the darkness, that orange glow on the horizon or reflecting from clouds above the trees.

Burning makes cropping much faster, and the sugar even tastes better, with a subtly caramelised tang to it. It also has the advantage of driving out snakes, making it safe for the croppers to enter. Sugar time, then, is when you’re most likely to see a python, and it’s also when they’re looking to eat before disappearing into the hills to meditate, as the Thais say, until the rains come back. Dogs disappear, and everyone has a snake story in their family.

Malayopython Reticulatus moved very, very slowly, and completely silently, getting itself into position. It watched the man intently as it moved. It knew from his breathing that he was deep asleep. Tongue flickering, it appraised his position, planning its move. It observed the man’s limbs, the left arm across his body, the right flung out above his head in sleepy abandon.

A hundred years it took, maybe two, but when it struck it was fast, closing like a sprung trap. Both ends of the snake entwined his body in an instant, the tail moving as intelligently as the head, binding him from knees to chest and crushing the breath out of him.

“Huuuuhhhh!” said the man, his eyes coming open.

“Wake up!” whispered the snake. “No time to sleep,” and sank its teeth into the shoulder of the free arm, whipping its neck muscles viciously from side to side like a dog, as if trying to tear the arm out of its socket. Clamped in a fifteen-foot coil of locked, constricting muscle, the man could not draw breath to make a sound as the animal ripped into his shoulder. Darkness welled up in his brain, feathering his vision as consciousness grew wings and prepared to float clear of his body.

But at that moment, his knuckles collided with the wooden handle of the knife, which lay exactly where he needed it to be, where he’d let go of it when he turned over.

He grabbed the handle and tried to stab at the snake, but he couldn’t get the point round because the blade was too long. So instead he drew the edge across the hard skin of the snake, sawing backwards and forwards, and for ten or twenty seconds that’s how they were, man and snake sawing away at each other until suddenly the coils loosened and unravelled like a shredded drive belt, and he could breathe.

“!hhhuuuuuuuH,” gasped the man, oxygen burning the light back into his eyes.

“Fuck you,” said the snake. “Now look what you’ve done.”

Ut hurled himself out of the hut, his left hand seeking the slippery meat of his right shoulder. Hugging himself like that, blood flowing through his fingers and down his arm, he staggered all the way back to the village, yelling raggedly for help. His son was at home, and he wrapped the shoulder in a wet T-shirt and drove him to Chum Phae hospital on the back of his motorbike.

“You were lucky,” said the medic who cleaned his wounds.

“I know,” said the farmer. “Lucky to get so drunk last night.”

“How so?”

Ut told him that they’d finished the sugar harvest yesterday and he’d sat up all night drinking with the driver.

The medic didn’t understand what that had to do with surviving the snake-attack, so Ut explained that he’d been cutting the sugar canes that the machine had missed at the edges of the field when he suddenly felt everything spinning and went to lie down in the hut.

“Ah,” the medic interrupted. “You see? So many ways Lao Khao can kill you. Like they say, if you don’t see the coffin, you never wake up.”

“What are you talking about?” said Ut. “Lao saved my life.”

“Oh yes? How do you work that out?” asked the medic. These farmers, they’re crazy, he thought.

Ut turned his head to look at him, just as he bent down to continue cleaning. “Because normally I keep my kni—”

Suddenly he stiffened on the table.

“Hurts?” asked the medic. Had the injection worn off already?

He looked at the man’s face and found that he was staring past him at something, with an expression of astonished horror on his face. He looked round, expecting to see a terrorist or a ghost entering the room, but there was nothing, only the glass door with the hospital logo. The man was trying to sit up, and he gently pushed him back down.

“Take it easy,” he said. “Relax.” Maybe hallucinating from loss of blood? Or just his sun-and-whisky-fried brain playing tricks on him. These farmers…

He started dressing the wound.

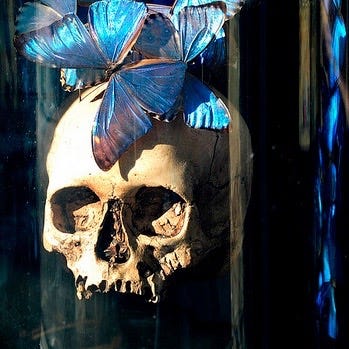

It was the first time Ut had been in a hospital. When he’d arrived he hadn’t noticed the strange symbol stencilled on all the doors. And there it was again, on the doctor’s badge, and again on the noticeboard on the wall.

A hundred questions raced through his mind. How did they know, ahead of time? And why put depictions of his ordeal everywhere like that, before he even arrived? Did they do that for everyone?

What is this place? he asked himself. Am I dreaming? Am I already dead?

The sun was getting close to the horizon as his son drove him home. Half the sky was obscured with dirty haze, the dark outline of Phu Wiang pillared with smoke. His shoulder was starting to hurt again.

“How many stitches?” asked his son.

“None.”

“Huh?”

“Not enough skin left to stitch! Stop at the shop,” he said. “I need a drink.”

“You have money?” asked his son.

“Sugar time,” said Ut. “Credit no problem.”

At home they hit the Lao together, and went over the whole story. When he got to the part about the strange depictions of his own near-death experience he’d seen painted everywhere at the hospital, his son frowned for a moment and then creased up, convulsed with laughter. Waving his arms, he gasped, “Pa! I can’t breathe!”

“Nor could I.”

And that started him off again.

The bottle was nearly empty. Ut hauled himself to his feet.

“Finish that,” he said.

As he lurched lopsidedly towards his bed, Ut turned and said, “You know what I think, son?”

His son was still shaking. “No, Pa, what do you think?”

“This life,” said his father, “—it’s just a crazy dream. Makes no fucking sense at all.”

Terrific story, love it.